Keeping Your Focus: Eye Care

Eye care in neuromuscular disorders

When people think about neuromuscular disorders, eye problems usually aren't the first thing that comes to mind. That makes sense, because most eye problems in neuromuscular disease are, thankfully, not too severe, treatable with therapy for the underlying disorder, or correctable with special lenses or surgery. But in some disorders, problems can persist, and they range from nuisances to major impediments to quality living.

Not too surprisingly, weakness of the muscles that control the eyeballs or those that open and close the eyes is probably the most common eye problem seen in an MDA clinic.

This weakness can stem from deteriorating muscles themselves, as in muscular dystrophies and other muscle disorders; abnormalities in parts of the brain that have to do with eyes and eye muscles, as, for example, in some mitochondrial disorders; or a problem in the communication between nerve and muscle, as is the case in various types of myasthenia. Results in all three types of weakness can be similar, but depend, of course, on the particular muscles involved.

Drooping lids: Surgery is easy 'when somebody knows how to do it'

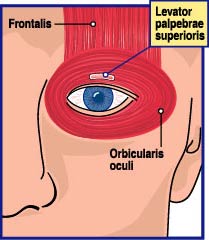

One muscle that's often affected has a long name with a simple meaning. It's called the levator palpebrae superioris, which literally means "lifter of the upper eyelid," and that's just what it normally does.

Weak levators are common in some neuromuscular diseases, particularly myotonic muscular dystrophy (MMD), myasthenia gravis (MG), congenital myasthenic syndromes, mitochondrial disorders and, most strikingly, in oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. In OPMD, as its name implies, weakness of ocular muscles is a defining characteristic.

When levators are weak, explains ophthalmologist Francois Codere, a condition known as ptosis, a drooping or dropping of the eye, results.

Codere, who practices ophthalmology and eye surgery at the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal, specializes in surgery to correct drooping eyes. He sees the problem frequently in Montreal, Quebec, in the heart of French Canada. Quebec has the highest OPMD incidence in the world.

Better understanding of the course of OPMD thanks to genetic and other discoveries in recent years has allowed surgeons like himself to better plan the nature and timing of a patient's surgery, Codere says.

One way to "strengthen" the levator muscle is by shortening it and pulling up on it. Known as a levator resection, this procedure is often done when levators are weak in stable, nonprogressive conditions. "If the levator is strong enough, we can just shorten it as you would tighten a loose elastic, by taking out a piece of it and reattaching it to the eyelid," Codere says. (The surgery doesn't really strengthen, but rather tightens, the muscle.)

But in most people with OPMD, particularly those whose course is predicted to progress rapidly (easier to do now, he says), the results are likely to be unsatisfactory.

"Since that muscle is sick in this disorder, and it's a progressive disorder, unfortunately that operation often only gives a temporary relief of the symptoms," Codere says. "It lifts the eyelid, but there's a tendency for it to droop again over the next five to 15 years."

For this reason, Codere prefers a different operation, called a frontalis suspension because it makes use of the large frontalis muscle in the forehead, which maintains its strength in OPMD.

For this reason, Codere prefers a different operation, called a frontalis suspension because it makes use of the large frontalis muscle in the forehead, which maintains its strength in OPMD.

Codere says, "The strategy is to use the movement of the brow and transmit it to the lid edge. The way we do that is by passing a kind of suspenders between the brow and the eyelid, so that when the patient lifts the brow, the lid edge will lift."

MDA grantee Guy Rouleau, a neurologist and neuroscientist at Montreal General Hospital and a colleague of Codere's, says such surgery can be "very, very effective" and usually lasts for many years. "In my experience, people do absolutely fine," he says, but notes that he's in a place where OPMD is well understood and easily recognized.

Problems sometimes occur with ptosis surgery when it's attempted by a plastic surgeon without much experience in the procedure, Rouleau says. He recommends finding someone who specializes in this type of surgery, such as an oculoplastic surgeon (Codere's specialty). "Up here, we see a lot of these patients, and the eye thing is a trivial problem, easily corrected. Well, it's easy when somebody knows how to do it."

Surgery, however, isn't for everyone. Sometimes a patient's condition isn't fit for surgery, and many times the weakness in the levators is rapidly progressing or fluctuating.

In some situations, such as myasthenic disorders (congenital myasthenic syndromes, which are genetic; or autoimmune myasthenia gravis, which results from an immune system attack on muscle cells), the solution is to treat the patient with medications and hope the eye problem clears up. It usually does.

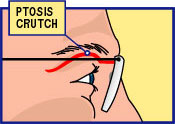

In the meantime, temporary solutions, such as "ptosis crutch" eyeglasses, can be employed. These support the eyelids for reading, driving or watching television. They shouldn't be used for too long a time at a stretch, because they can lead to drying of the eye, but they work well for some situations and some patients.

Of course, some people bypass fancy solutions.

"I had an older myasthenic patient, a man in his 70s who ended up using Scotch tape on his lids," says neurologist David Chad, who directs the MDA Clinic at University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care in Worcester. "That's the crutch I'm most familiar with. The only worry is that if you keep the eye open, you can have a corneal abrasion [scratch on the cornea, the covering of the eyeball]. But a lot of ophthalmologists hesitate to do surgery in this disorder because of the fluctuating course."

"I had an older myasthenic patient, a man in his 70s who ended up using Scotch tape on his lids," says neurologist David Chad, who directs the MDA Clinic at University of Massachusetts Memorial Health Care in Worcester. "That's the crutch I'm most familiar with. The only worry is that if you keep the eye open, you can have a corneal abrasion [scratch on the cornea, the covering of the eyeball]. But a lot of ophthalmologists hesitate to do surgery in this disorder because of the fluctuating course."

In children, a severely droopy eye can affect development of the still immature visual system. The brain needs normal visual input from an open eye in order to develop all the right connections between the eye and the brain (see "Lazy eyes" section below). For this reason, it's crucial to treat a droopy eye in a child if at all possible.

When eyes won't close: Prevention better than treatment for dry cornea

The muscle that closes the eye is a circular one (see illustration above) called the orbicularis oculi, Latin for "little circle around the eye."

Weakness of this muscle doesn't occur as often in neuromuscular disease as does weakness of the levator palpebrae, but it can be a problem, particularly in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. In this form of MD, which involves weakness of several facial muscles, weakness of the orbicularis oculi muscles can keep the eyes from closing completely. That can be a serious problem during sleep, because the cornea — which covers the front of the eyeball like the glass on a watch — is left partially exposed all night, allowing it to become dry or scratched.

Eye surgery to lift the upper eyelid, if done incorrectly so that the lid is pulled up too high, is another common cause of difficulty with eye closure.

Symptoms of a dry cornea are a gritty or burning sensation in the eyes, as well as red or watery eyes.

Incomplete eye closure can be managed by wearing an eye mask during sleep and lubricating the eye with drops or ointments during the day and before sleep, Codere says.

A dry cornea can become infected — a "disastrous" situation, Codere notes, one that's better avoided than treated. In extreme cases, the patient may have to wear goggles to keep moisture from evaporating around the eyes, at least temporarily. Surgery to lift the lower lid can be done, but results aren't always satisfactory.

|

| Six extraocular muscles — four straight and two diagonal — surround each eyeball and allow it to move in all directions. Weakness in any of these can lead to an inability to move the eyes or, if the two eyes are differently affected, to strabismus. |

Lazy eyes: 'Don't make two problems if you only have one

Most neuromuscular conditions affected muscles that are considered voluntary — that is, those that can be moved at will. Such muscles share a similar structure and function, and look similar under the microscope. But not all voluntary muscles are exactly the same.

The extraocular muscles, six small muscles that move the eyeball in all directions, are voluntary muscles, but they have characteristics that make them slightly different from other such muscles. That may explain why they're particularly hard hit in some neuromuscular conditions, such as the myasthenias, mitochondrial disorders, myotubular myopathy, OPMD, myotonic dystrophy and thyroid-related muscle disorders. It also may indicate why they're almost never involved in Duchenne or Becker muscular dystrophy, limb-girdle muscular dystrophies, the merosin-deficient form of congenital muscular dystrophy, or the motor neuron disorders spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

There are six extraocular (EO) muscles for each eye — four straight, or rectus, muscles; and two slanted, or oblique, ones. Normally, the EO muscles work together with each other and with the muscles of the other eye to allow the gaze to be focused in any direction and to ensure that both eyes are sending the same image to the brain.

When one or more of the EO muscles weakens, the eyeball can't be moved in the direction in which that muscle would normally move it, such as upward (superiorly), downward (inferiorly), inward toward the nose (medially), or outward toward the ear (laterally).

If EO muscles in both eyes weaken at about the same rate and in the same way, there isn't much to worry about, says Andrew Lee, a neuro-ophthalmologist — eye doctor who specializes in eye-brain interactions — at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics in Iowa City.

Fortunately, says Lee, that's usually the case in neuromuscular disorders. EO muscles may weaken, but they tend to weaken equally in both eyes. Such patients don't need to have eye muscle surgery, he says, because, although the eyes are unable to move, they're equally unable to move.

People with this condition "just turn their heads to see," Lee says. "They just pick their heads up or turn the head from side to side to see in different directions. If it's been like that for a long time, they just get used to it. Many patients don't even know that their eyes don't move."

Trouble comes when EO muscles in the two eyes don't weaken the same way or at the same rate. That causes a condition known as strabismus, meaning eyes that can't focus on the same object at the same time.

People with strabismus see one image with one eye and get a slightly different view with the other eye, sending two images to the brain. The result is double vision (sometimes of the same object, sometimes of different objects, depending on the type of weakness).

After childhood, double vision is a nuisance but not an emergency, because double vision that begins in adolescence or adulthood isn't likely to damage the visual process itself. In childhood, however, the situation requires immediate attention.

A simple treatment for double vision that starts after childhood is to block the vision from one eye, which can be done by wearing a patch or, more elegantly, a lens that looks transparent from the outside but blocks vision from the inside (called a Min lens, for its inventor).

In some cases, prism lenses can help align the eyes. These can be ground into the eyeglass lenses, if the problem is stable, or applied to the glasses as a thin, sticky sheet, if the problem is thought to be temporary or fluctuating. (These last are known as Fresnel prisms, after a company that distributes them.)

A new treatment for some kinds of strabismus is botulinum toxin, a bacterial poison that weakens muscles. It can be injected into a muscle that's too strong (pulling too tightly) to temporarily weaken it and thus straighten the eyeball. It's not a permanent solution, but it's useful in certain circumstances, particularly if surgery can't be done.

As in ptosis treatment, EO muscle weakness in myasthenias and thyroid-related myopathies can often be corrected by treating the underlying disease with medication.

If medications aren't effective and the eye muscles aren't expected to change much over the years, surgery to correct strabismus can be undertaken.

In children, strabismus is more serious, requiring immediate action. The reason for the urgency is that the child's brain is still developing, with connections between the eyes and the brain still forming up to about age 8 to 10.

When the brain receives two separate images, an uncomfortable situation for it, it simply shuts off the image from one eye. If that condition persists for a while, sometimes just a few weeks in young children, vision in the "rejected" eye is likely to be damaged. The resulting condition is known as amblyopia which literally means "dull eye" but is more often called "lazy eye."

Lazy eye isn't really eye damage, but a form of brain damage, in that the developing brain stops processing images from the eye it's decided to ignore and ultimately loses the ability to do so. Eye-brain connections in adolescents or adults are stable enough so that strabismus doesn't cause amblyopia. By the same token, however, amblyopia that starts in childhood isn't likely to be correctable with interventions after childhood.

Lazy eye is probably most often associated with strabismus, but it can also result from ptosis or from anything that interferes with the visual signals the brain normally receives from each eye during childhood. Keeping an eye covered can also cause amblyopia, which is why care has to be taken with therapies that involve patching of children's eyes.

"With children," cautions Lee, "it's urgent to prevent lazy eye if they have a droopy eyelid or a crossed eye. Don't make two problems if you only have one. If you wait until the child is older to correct the problem, you might have a lazy eye on top of, for example, congenital myasthenia. All these children should be examined and treated when they're young."

The treatment may ultimately be surgical, if the strabismus or ptosis is considered stable, but other therapies can also be used, in addition to or instead of surgery.

Most children with strabismus or ptosis in one eye will undergo treatment to patch or in some other way block the vision in one eye (for example, with Min lenses), forcing the brain to process signals from the eye it's been ignoring. To avoid amblyopia in the blocked eye, a careful schedule for the patching or blocking has to be followed.

Other vision problems: Not common, sometimes treatable

Neuromuscular disorders are more likely to affect the muscles that move the eye than they are the structures of the eye itself, but there are exceptions.

In myotonic dystrophy, a disorder that affects many organs, cataracts are found in nearly everyone. These are cloudy or scratchy spots on the eye's lens that can, as they increase in severity, interfere with vision. Fortunately, they can almost always be safely removed or dissolved and an artificial lens inserted.

Precautions with respect to anesthesia are important when anyone with a neuromuscular disease, particularly myotonic dystrophy, has surgery. The neurologist and the surgical team must consult before any procedure is undertaken.

Precautions with respect to anesthesia are important when anyone with a neuromuscular disease, particularly myotonic dystrophy, has surgery. The neurologist and the surgical team must consult before any procedure is undertaken.

Cataracts can also occur as a side effect of prolonged treatment with corticosteroids, the prednisone family of drugs. These are often used in inflammatory myopathies, autoimmune MG and Duchenne MD.

The eye's retina isn't often a target of neuromuscular disease, but it can be in mitochondrial disorders. Websites and print materials unfortunately sometimes describe the problem as retinitis pigmentosa, which, if the reader looks it up, describes a group of genetic eye diseases, several of which can lead to blindness with time.

A better term is pigmentary degeneration of the retina, says Robert Daroff, a neuro-ophthalmologist at University Hospitals of Cleveland, and the problem usually doesn't lead to blindness, although it can lead to poor vision.

Some mitochondrial disorders, such as Leigh's syndrome, can affect the optic nerves, "cables" that carry information from the eyes to the brain. This, too, can interfere with vision.

Neither Daroff nor David Chad has seen many neuromuscular patients with vision-threatening problems in their many years of practice. Daroff notes that vision problems in neuromuscular disease in general tend to be minor and pose less of a threat to one's quality of life than do other issues in these disorders. "I don't think patients should be overly sensitized about this," he says. "But if they have trouble seeing, they should see an eye doctor."

Parents, he says, should be on the lookout for crossed eyes or droopy lids in their children, and for the child who continually bumps into things or holds his head in an odd position and resists having it straightened. "Amblyopia," he says, "is absolutely avoidable."

Saving Vision in a Child with Myasthenia

Brittany Duncan is like a lot of energetic 10-year-olds in Linden, Texas, a town of about 3,000 people near the Arkansas border. But Brittany has had troubles not common in her age group.

"It was kind of hard for me in the beginning," Brittany says, "because I didn't understand. I didn't know what was happening until my mom talked to doctors, and they told us about it."

"It" is something Brittany sometimes refers to as "the monster" — her myasthenia. The type of myasthenia — which means weakness due to a defect in nerve-to-muscle signal transmission — isn't clear in Brittany's case. It may be the autoimmune type, usually called myasthenia gravis, or it may be a genetic type, often called a congenital myasthenic syndrome.

Brittany's mother, Jo Anna, a former high school biology teacher, thought something was wrong when she noticed that her 4-month-old daughter's left eye would droop whenever she was tired or had a fever.

Trips to the family doctor and even an eye doctor didn't immediately yield any answers, but at about a year, an ophthalmologist at Arkansas Children's Hospital in Little Rock diagnosed Brittany's condition with a Tensilon test. When he administered the drug, which fleetingly increases the amount of the nerve chemical acetylcholine reaching muscle cells, "immediately that eye just fanned open like a rose blooming," Duncan says.

For a few years, Brittany's condition was stabilized with Mestinon (pyridostigmine), a drug that works like Tensilon but with a much longer action. As time went on, though, the myasthenia became more severe and involved more muscles. The Duncans took Brittany to the MDA clinic in Shreveport, La., where they got more advice and support for the generalized myasthenia, but they stayed with their Little Rock ophthalmologist for Brittany's eye problems.

At age 4, he noted that her vision had deteriorated and that the muscles controlling the eyeball weren't behaving properly. Brittany was at high risk for amblyopia (see "Other vision problems" section above).

"He felt we needed to do surgery," Duncan recalls, "because the eye had drooped so much that it had caused the eyeball to wander around. It was like her brain was trying to opt for ways to overcome the drooping.

"I was terrified [about the surgery], because I had always been told that myasthenic patients were never to have anesthesia. It was a scary time for us, but the ophthalmologist said, 'I just want her to be able to see better and for that eye to look better. She's too beautiful to have her eye look like that.'"

Because of good planning and awareness of Brittany's myasthenia on the part of the surgical team, the operation went fine. However, about a year later, the other eye started to "wander upward," Duncan recalls.

The second surgery was also a success. "It took her a good month to get over it and get back to being active again," Duncan says. "But she handled it. Her vision is much better now."

Brittany has glasses to further improve her vision, and recently switched to contact lenses, which she prefers.

A Child Copes with Low Vision and Mitochondrial Disease

Carl Mason was 18 months old when his mother, Terri, began to notice that his eyes were always wiggling back and forth, a symptom known as nystagmus.

"It was worse in some positions than others, but it was happening pretty much all the time," Mason remembers. "We went to the ophthalmologist, who did a complete eye exam and thought it might be a brain tumor. We ruled out the brain tumor with an MRI scan, and they had us come back every couple of months for a while."

"It was worse in some positions than others, but it was happening pretty much all the time," Mason remembers. "We went to the ophthalmologist, who did a complete eye exam and thought it might be a brain tumor. We ruled out the brain tumor with an MRI scan, and they had us come back every couple of months for a while."

On one of those visits, the eye doctor noted something else: The optic nerve in each of Carl's eyes was getting smaller (atrophying), and he was losing vision.

"The nerves continued to atrophy for about a year, at which time they stopped. His vision has been stable since then," says Mason, "but it's about 20/250 [meaning he has to be at 20 feet or closer to see something most people could see from distance of 250 feet], and they can't correct it."

Carl's diagnosis eventually became clear. He has Leigh syndrome, a mitochondrial muscle disorder that can affect the visual system.

Carl is now 8, and although his disease continues to take its toll on many of his functions, he also seems to be showing signs of improvement.

"When Carl first lost vision, his vision measured much lower than it does now because he didn't know how to use what he had," Mason says. She attributes much of that knowledge to the help of vision teachers, certified specialists who have helped Carl through the public school system in Portland, Ore., where he's now in a special education classroom in second grade.

Vision teachers, Mason explains, teach the child to use the vision he or she has rather than focusing on improving vision. They teach orientation and mobility — "how to get from point A to point B," Mason says — and help the child become as independent as possible. They look at classroom materials to see which ones need to be modified, and make sure that a child has the right computer keyboard and monitor.

"When we first found out, the tendency was to protect him," Mason says. "But you can't hover. I did that for a long time. I would hover at the jungle gym waiting to catch him if he fell. But they're really a lot more resilient than you think they are. You can back off more than you think before jumping in to help."

Carl is doing better than expected for someone with his diagnosis, Mason says. He's gotten weaker, but he can still walk, and she believes his IQ test will show improvement this year.

"Carl has an incredible sense of direction," she says. "Whenever we go to a doctor's office, I invariably get lost in the maze of hallways. He'll lead me out every time."

Tired of Band-Aids, Counselor Plans Eyelid Surgery

Linda Stullenbarger wasn't bewildered by what was happening when her eyelids began to droop about four years ago.

"Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy is very prevalent in my family," says the 58-year-old counselor from Wheeling, W.Va. "The person who brought it into the family was my maternal great-grandmother, as far as I know. She had brothers with it, and out of her nine children, I think seven of them have been shown to have had it.

"Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy is very prevalent in my family," says the 58-year-old counselor from Wheeling, W.Va. "The person who brought it into the family was my maternal great-grandmother, as far as I know. She had brothers with it, and out of her nine children, I think seven of them have been shown to have had it.

"Back then, nobody knew what was wrong, but my mother had wonderful old pictures, and I noticed lots of droopy eyelids," Stullenbarger says. "I can remember my grandfather sitting with a sort of cap on, with it placed down over his eyelids and pulled up in such a way that it would open his eyes. I have a picture of him."

For Stullenbarger, droopy eyelids aren't just an inconvenience or a cosmetic problem; they're also a professional handicap.

"I'm an adolescent specialist. When somebody new comes in, I have to explain it to them. I've been asked, 'Are you going to sleep? Are you tired? Maybe I should go?'

"I just tell them, 'I have a late-onset type of muscular dystrophy, and one of the things with it is that my eyelids droop, so I want you to know that you're not boring me or making me sleepy or tired.'

"It's hard to explain, though. When you're working with people, you really use your eyes and your expression with them. You want to use your voice, your body, your eyes. You're attending to these people, trying to be with them, with what they're trying to say. I don't know how my facial expressions come across to them."

Stullenbarger says she's heard some "nightmare stories" from family members who were unhappy with their ptosis surgery, and she wants to be sure she gets the right kind of surgeon to do hers. But she doesn't want to put it off much longer.

A recent experience made her laugh, but also brought the problem home to her. "I started on a trip to see my brother and sister, who live about four hours from here. I was driving after dark, and I couldn't see. I stopped and looked around in my purse and found two Garfield [the cartoon cat] Band-Aids, which I used to tape up my eyes.

"Then I had to stop on the way to go to the bathroom, so I stopped at a McDonald's with these Garfield Band-Aids on my eyelids. I had nothing else, and I had half a trip to go. I had to see. But people were just kind of going 'Um-hm.'"

Becoming more serious, Stullenbarger says she now knows what her mother must have gone through.

"When my beautiful mother, a very lovely woman, got older, her eyelids were so bad that she started wearing sunglasses, even to church. I asked her why, and she said it was because she looked so ugly. I said she could never look ugly, but now I understand what she meant.

"You do feel kind of different. My husband and my doctor are the only people who see me without makeup now, and I want to go through our church directory with a hole puncher and punch out all my photos. I used to have very bright, wide open eyes. The droopy lids change the whole appearance of my face."

MDA Resource Center: We’re Here For You

Our trained specialists are here to provide one-on-one support for every part of your journey. Send a message below or call us at 1-833-ASK-MDA1 (1-833-275-6321). If you live outside the U.S., we may be able to connect you to muscular dystrophy groups in your area, but MDA programs are only available in the U.S.

Request Information